In this episode of The Writing Coach podcast, writing coach Kevin T. Johns introduces his new Scene Alchemy Essentials Checklist tool and discusses the importance of:

- Scene length

- Point of View

- Stakes

- Internal and External Conflict

- Causality

- Setting

Listen to the episode or read the transcript below:

The Writing Coach Episode #171 Show Notes

Download the FREE Scene Alchemy Essentials Checklist Now!

The Writing Coach Episode #171 Transcript

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

Hello, beloved listeners. And welcome back to The Writing Coach podcast. It is your host, as always, writing coach Kevin T. John’s here.

I am recording this early in September. Story Plan Intensive is underway. We’ve got a great group of writers in the program and an even greater group of writers in the group coaching. So excited to be working with all of you this month.

We are getting ready to open the doors to my group coaching program, FIRST DRAFT, later in the month. We’re going to open it up for a cohort of writers, so if you’re interested in hearing about FIRST DRAFT and what we have to offer, head on over to www.kevintjohns.com/firstdraft. But FIRST DRAFT is not what we are going to be talking about today.

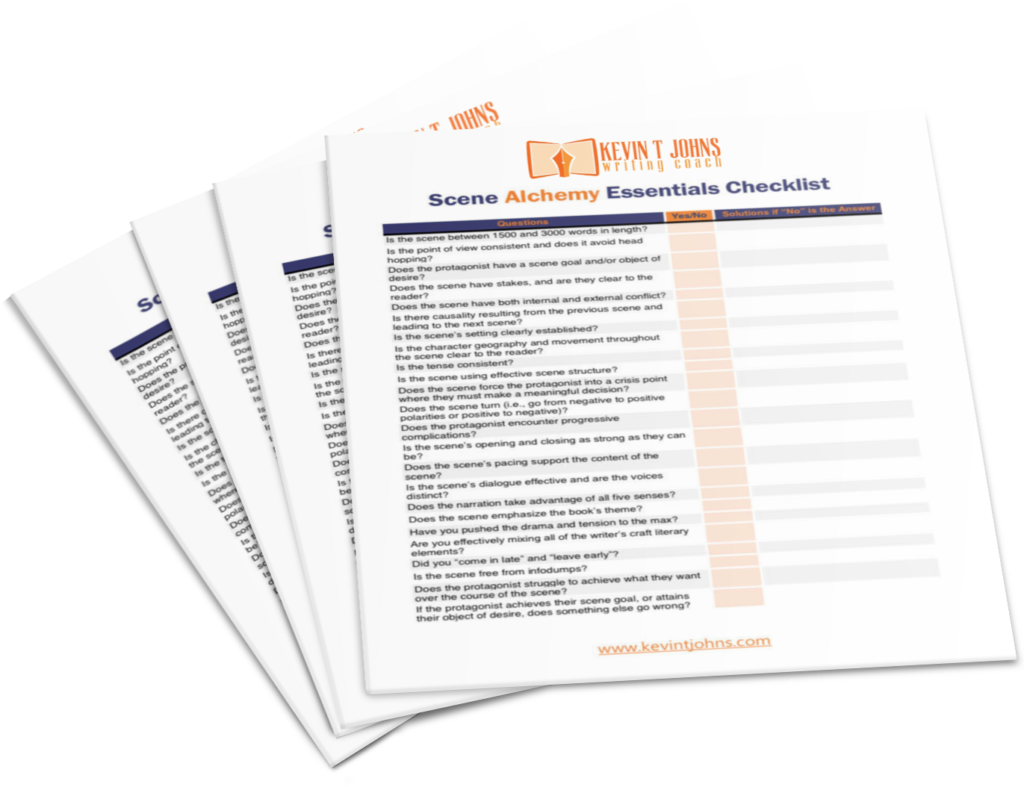

I am super excited because today I am sharing with you a new gift, a new giveaway, that you can pick up on my website. It is called “The Scene Alchemy Essential Checklist.” You can download that checklist here.

Now, so many writers come to me, and they’ve written scenes, or they’ve written books, and they know it’s not good enough, but they don’t know how to make it better. They want it to be gold, but it’s bronze. And so that’s where “The Scene Alchemy Essential Checklist” comes in. It is a series of over 20 questions you can ask yourself about any given scene in your book. And if you can answer “yes” to as many questions as possible, you can transform that scene, that mediocre scene, that okay scene, into literary gold, into a top-notch scene. Now, there are a lot of questions, as I said, so we are going to tease them out over the next couple of episodes of the podcast so that you can effectively use the checklist to improve your work.

That said, these are big issues, and we’re only going to be able to touch on them quickly here. In FIRST DRAFT, we do have training courses that cover every question in this checklist. So, if you do want a longer course and more training on these issues, again, check out FIRST DRAFT. But for now, I think we’ll be able to talk through each question in the checklist to the point where you are going to understand why the question is being asked and then execute on improving your scene by getting the answer to that question to a “yes.” Does that make sense? I hope it makes sense. It’s going to. It’s going to, so go download the checklist and then listen to this episode, and we are going to have you rocking and rolling in no time.

Now, the first question on the scene alchemy essentials checklist is:

Is the scene between 1500 and 3000 words in length?

What I find is that scenes under 1500 words might be lacking something. You might not have got enough physical description in the scene, you might not have got enough environmental description, and you might not have pushed the conflict far enough. What I like to think of is a scene is like a wet washcloth, and when you’re revising a scene, you really want to twist that washcloth and get every little drop of drama and emotion out of that scene. If your scene is less than 1500 words, there’s a chance you’re not getting all the juice out of it that you might be able to get.

If the scene is over 3000 words long, you might be losing the reader’s attention, and the scene’s energy might be starting to lag. Can there be super incredible, dramatic, exciting scenes over 3000 words? Absolutely. Of course. Can there be scenes that are super effective at less than 1500 words? Of course, but what this checklist does is allow us to do a little check for ourselves and say, hey, if it is over 3000 words, are we sure it’s maintaining the reader’s interest? If it’s under 1500 words, are we really getting the most out of the scene that we can get?

I like to think about shooting a movie. I guess not everyone has worked on a movie set, but I think people have a general sense of how movies work. Say we’re shooting a diner scene, someone has to build an entire diner. They spend weeks building it, getting the set together, and filling it with props. And on the day of the shoot, everyone’s showing up, and we’re lighting the diner. And we’re figuring out where the actors are going to be in the diner, or we’re figuring out where the extras are going to be.

Or we’re using an existing diner, which means a crew of a couple hundred people are probably travelling to this location. We need to find parking, we need to shut down local traffic, and we need to make sure we have generators on site so we’re not blowing the electrical power grid.

The point is that shooting a diner scene is a ton of work. And so you can bet in cinema, if they’re going to spend days and time and money to create that scene, they are going to make sure they get every production dollar they can out of that scene.

Whereas because novelists have an infinite budget, I find sometimes my clients aren’t using their scenes and their location for all that they’re worth. If you are going to write down a scene, ask yourself if this was a scene in a movie, would it be worth 200 people driving somewhere to shoot? Or would it be worth spending a month building the set and filling it with props? Make sure that your scenes are as robust and as effective as they can be. Don’t shortchange yourself by writing too short a scene.

Okay, that’s question number one. As you can see, we have got a lot of questions to cover. We’re going to do a couple of episodes here. Question number two:

Is the point of view consistent, and does the scene avoid head-hopping?

Now, this is probably the number one issue I encounter when first-time novelists come to work with me. They’ve written a manuscript or they’ve started a manuscript, they hand it over to me for review, and literally, the first thing I’m looking for is the point of view. Is it third-person limited? Is it first-person limited? Usually, it’s not. Usually, it’s some sort of quasi-omniscient slash third-person slash head-hopping. And it can take a lot of work to rein that in or even to understand the concept of point of view.

It may sound easy, but it’s not. Beginner writers really can struggle with it, and even advanced writers and that is why it’s here on the checklist. I’ve seen writers so many times fall into first person and not even realize they’ve done it, or much more often, accidentally head-hop or accidentally fall into omniscient narration in a third-person limited book.

The head hopping thing, it’s so hard for beginner writers to get their head wrapped around. Is that a Freudian slip? They have a hard time getting their head wrapped around head-hopping. The reality is that readers hate head-hopping. Literary agents hate head-hopping, and editors hate head-hopping. Publishers hate head-hopping and the dog on the street who uses the book as toilet paper! I don’t know. The point is, No one likes head hopping except beginner writers because they want the reader to see what everyone’s thinking and everyone’s feeling. But that’s not effective storytelling. It distances us from the protagonist. It can be super confusing because we don’t know who is saying or thinking what. There are some other elements in this checklist, like polarity shifts, that become almost impossible to track if we are not limited to a single character’s POV or if we are not at least locked into a consistent, omniscient point of view. And again, even omniscient is not an excuse to be willy-nilly head-hopping.

So, after you write a scene, get out “The Scene Alchemy Essential Checklist” and review your point of view. Make sure you are sticking with the book’s chosen point of view, and make sure you are not head-hopping.

Next up:

Does the scene have stakes, and are they clear to the reader?

Stakes are the consequences of our protagonist or point of view character not attaining or achieving what they’re trying to achieve. Quite often, we have scenes where characters want something, but as authors, we fail to articulate for the reader what it is they want or what it is they’re trying to get out of any given scene. And more importantly, we’ve also not made it clear to the reader what the stakes are. So we need to lock that down. Because the tension, the drama, the conflict exist in relation to the results.

If we’re writing a romantic comedy and a girl is going to ask a guy on a date, if we don’t understand what the consequence of him saying “No” to that date, as well as the consequence of saying him “Yes,” then we don’t understand the drama of the scene. Stakes are important for establishing what’s at risk at any given moment in a book and for emphasizing the significance of every little moment.

Look at your scenes and say, are there stakes? Are they significant? And if they are, have they been made clear to the reader? Sometimes, as authors, what seems very clear to us is not always clear to the reader. Ask yourself, if a reader reads this scene cold, would they understand what’s at stake?

Does the scene have both internal and external conflict?

Drama is about conflict. But that does not have to be a person escaping a burning building; that’s external conflict, but conflict can also be a person asking themselves if they’re deserving of love or not, or if they should choose to be alone, or if they should choose to join a group or reject that group. Internal drama and internal conflict can be just as exciting as external conflict.

You’ve probably heard the distinction between commercial fiction and literary fiction. The clear demarcation between these two kinds of big categories of books is that commercial fiction tends to focus on external conflict characters doing things out in the real world, trying to rescue people from burning buildings, or trying to go on a date and have sex or physical external elements of the story. Whereas literary fiction is much more internally focused, the conflicts are within our characters.

When we look at something like Mrs. Dalloway, all of the conflict in that story, for the most part, is happening inside the characters’ heads. We have a World War I shell-shocked veteran in that book, and the war is over. He’s not dodging bombs, he’s not firing guns from the trenches of World War I. That’s external conflict, but that’s not what Mrs. Dalloway is about. It’s about the internal struggles he’s dealing with because of shell shock and of the traumas and horror of World War I.

Now, you might think, “Oh, okay, so literary fiction is all internal and commercial fiction is all external.”

Not at all. We want both in every story. Yes, if you’re writing a vampire story, it’s probably going to lean more on external conflicts than it is on internal. But the story still needs internal drama, it needs to feel like people are going through emotional and intellectual challenges. And in the same way, on the literary side of things, yeah, we might be able to get away with a scene of someone looking at a window and thinking for an entire scene, but you can’t get away with a whole book of that. People still need to go out and do things. The Life of Pi is a literary book, but we still get tigers and boats and desert islands and all of these things, right?

Most of the people I work with tend to be writing commercial fiction, in which case, they almost always have good external conflict already. If not, here’s the chance to look at that scene and get that external conflict in there. But like I said, often with my commercial clients, it’s already there. So we want to ask ourselves, what’s the internal conflict? What’s going on inside of our characters? It might be just as interesting as what’s going on outside.

Is there causality resulting from the previous and leading to the next scene?

How we want our story to unfold is to feel like a series of dominoes falling. We want every scene to feel like it couldn’t have happened without the previous one happening. And we want scene three to feel like it couldn’t have happened unless scene two happened. We want that causality, most of the time, throughout the entire book. That’s what creates a page-turner. That’s what creates great pacing. When people say, “I couldn’t put the book down,” it’s because every scene leads to the next scene, and every conflict leads to the next conflict. And that’s how we want to pull readers through a book.

When you’re sitting down to look at a scene, and you’re saying, “Is the causality here?”, a way to ask yourself this question, another way to phrase it, is to say, “If I took this scene out of the book, would it significantly change the book?” If not, then that scene probably shouldn’t be in there. It’s probably slowing down the pacing. It’s probably just providing exposition or a character moment. Or maybe you’re going on a little tangent. We want our stories structured so that if we take any one given scene out, the whole narrative falls to pieces because every scene should be set up by the preceding scene, and every scene should lead into the next scene.

All right, let’s look at our last question for this episode. Our last question from “The Scene Alchemy Essential Checklist” is:

Is the scene’s setting clearly established?

Again, this is something that I see people miss a lot or just save till revisions, which I think is perfectly fine.

I don’t necessarily dig writing environmental descriptions in my novels, at least certainly not during a first draft. I want to focus on the adventure, I want to focus on the emotion, I want to focus on the drama. But that can’t exist in black space.

We need to understand where the scene is taking place. Are we inside? Are we outside? Are we on a boat? Are we in an airplane? If we’re in an airplane? Are we in the cockpit? Are we in the bathroom? Are we in the area where the stewardesses get food ready? Or are we sitting in a seat looking out a window? The environment in which a character interacts with the external world and with other characters matters. So, in revisions, I get in there, and I start fleshing out those environments.

Environments can be so important to the point where they can become characters themselves. You think of any sitcom you’ve ever watched. Let’s talk about Friends. Those apartments in Friends and the Central Perk location feel almost as essential to the show as the characters. it would feel weird if they suddenly had a new coffee shop, just as weird as it would feel if they replaced Monica with a new actress. Location and environment matters.

If you are the type of writer who already gets that established when you’re in your first draft, awesome. But so many of us can come back in revisions, and we can pull out the scene this checklist, and we can remind ourselves to ask ourselves, “Is the scene’s environment clearly established?” so that we can really build that world for the reader and so that we can clearly have our characters existing in a place and time. The second it starts feeling like the characters are just heads floating in space, we’ve lost the physicality of the scene.

Often, I see writers opening scenes with these kind of recap paragraphs that will say, “It was two days before the letter finally arrived in the mail.” And while I’m hearing that, I’m like, where’s this happening? Who is this narrator? It’s just a voice floating in black space. Much more often, I would prefer you start the scene with a character clearly rooted in a specific place and time. Absolutely, we’re going to go into some exposition at some point, and we’re going to go into some internal narration, but before we do that, tell me where this scene is taking place. Tell me about the environment that is taking place in.

All right. I hope you found that helpful. That was the first six questions in the “The Scene Alchemy Essential Checklist.” It’s a free resource that I’m giving away, and you can get it here.

Thank you so much for tuning in. We are going to continue to go through that checklist, so make sure you hit that subscribe button so that I can see you on the next episode of The Writing Coach.