In this episode of The Writing Coach Podcast, writing coach Kevin T. Johns discusses Star Wars, punk rock, and how writers should consider desperation as a preferable alternative to perfection.

Listen to the episode or read the transcript below:

The Writing Coach Episode #162 Show Notes

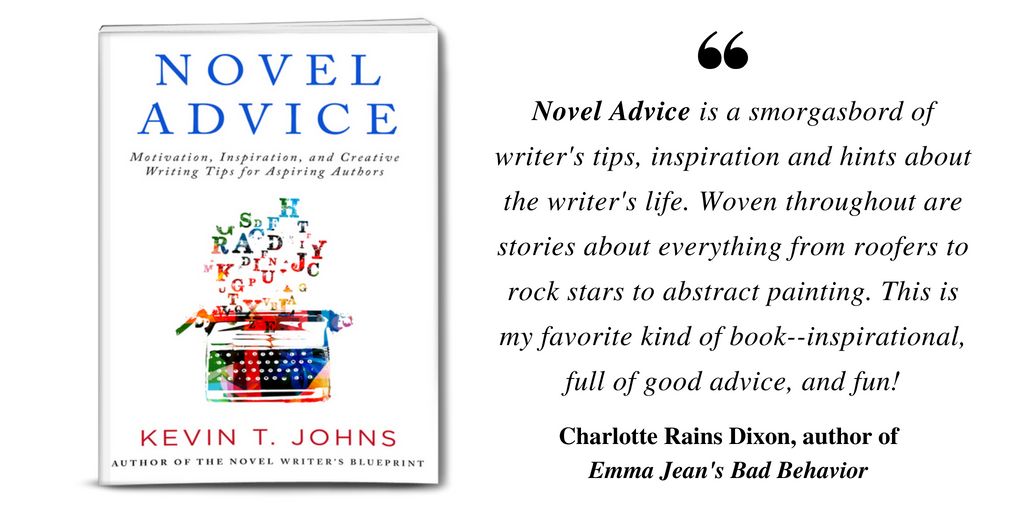

Get Kevin’s FREE book: NOVEL ADVICE: MOTIVATION, INSPIRATION, AND CREATIVE WRITING TIPS FOR ASPIRING AUTHORS.

The Writing Coach Episode #162 Transcript

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

Hello, beloved listeners, and welcome back to The Writing Coach podcast. It is your host, as always, writing coach Kevin T. John’s here.

In addition to being a podcast host and a writing coach, I’m also an author. And one of the books that I have out there for writers is a book called Smash Fear and Write like a Pro. It is so short, it’s like 10,000 words, 12,000 words, this little piece of motivational, inspirational advice about facing your fears as a writer, it’s available on Amazon. I’ll link to it in the show notes for this episode. This is episode 162 of the writing coach podcast, head over to www.kevintjohns.com and you can find those show notes and get the link to my book, Smash Fear and Write like a Pro.

I tackle five fears in that book. And one of the fears that I tackle is the fear of releasing your work before it’s perfect. And one of the stories I tell is about George Lucas, my man, the creator of the original Star Wars trilogy. For years, he wasn’t happy with those films. He felt like they weren’t perfect enough. So what he did in the mid-90s, as special effects were getting better, is he went in and he changed the original Star Wars films, and he released them as the Special Editions.

Now if you were around back in the day, you might recall how audiences responded to these special editions. They hated them. “Han Shot First” became a meme. And that was really the beginning of people starting to attack George Lucas. And, of course, it only got worse when the prequels eventually came out.

But my point is, Star Wars was already perfect. That’s why people were so upset. George Lucas was going in and changing something that didn’t need to be changed. Now in his mind, in the mind of the artist, the work was incomplete, the work wasn’t good enough, but in the minds and hearts of millions of cinema goers and fans of Star Wars like myself who grew up with these films, changing them with sacrilege.

This is the danger of giving in to this perfectionist streak — this idea that, “Oh, what I create is never good enough. I need to go back and fix it and make it even better.” It’s almost never a good idea.

I’ve spent a lot of time almost two decades doing work with the Canadian federal government, a huge, hierarchical organization. I’ve also ghostwritten several books for top executives in big giant companies. And what I’ve seen almost across the board is that the people who define themselves as perfectionist are almost always the lowest-ranking people in any given hierarchy. I’ve never heard an executive call themselves a perfectionist.

In fact, in the great film Danny Boyle’s Trainspotting, based on Irvin Walsh’s seminal novel, there’s a scene where the characters in order to stay on welfare, they have to make it look like they’re trying to get jobs. They go to these job interviews, but they intentionally tank them. And one of the ways that they intentionally tank the interview is one of the characters describes himself as a perfectionist. He’s clearly a junkie, he may be living on the street, but he’s coming in, and he’s telling these people that he’s a perfectionist. The humor here is double-fold. It’s funny because he’s obviously not a perfectionist. But it’s also funny because calling yourself a perfectionist is the type of thing you can do if you want to get yourself fired.

People at the top of the hierarchy know that perfection is rarely possible to achieve. And trying to do so is extremely inefficient. It’s an inefficient use of energy, of resources, of time to try to get something from 95% good to 95.5% Good.

Plus, not only are rough edges acceptable practically all of the time, but sometimes rough edges are preferable.

Now this is something that I talked about in an episode called “10 Lessons Writers Can Learn from Punk Rock.” And I talked about this idea that I learned the importance of rough edges from punk rock. And as we return to this perfectionism discussion, I think we need to go back and revisit punk rock and some of the lessons we can learn from it again.

The other night, I was on my phone watching music videos on YouTube and I came across a video of the band Primus doing a cover of the punk band The Dead Kennedys’ song “Holiday in Cambodia.” It was okay. The bassist of Primus, Les Claypool, is one of the greatest bass players ever and the cover was okay.

Having watched that video, it then led me to a video of the band, the Foo Fighters, joined by the singer of System of a Down, and together, they were doing a cover of “Holiday in Cambodia.” And so I watched one of the best bass players ever covering “Holiday in Cambodia” with Primus, and then I watched one of the most renowned rock bands ever, Foo Fighters, with the singer of the renowned System of a Down doing a “Holiday in Cambodia.”

Despite the fact that these were some of the greatest musicians out there, neither of their covers even came close, in comparison, to the quality of the original song made by a bunch of scrappy 20-year-old punk rock kids with crappy equipment in 1980.

Why were these punk kids able to create something so magical that bands like Primus and Foo Fighters weren’t able to recapture in their rendition of the song?

I think the answer to that question is the alternative to perfection.

And that’s desperation.

In 1997, the punk band NOFX released their album So Long and Thanks for All the Shoes, and that album included a song called “The Desperation’s Gone.”

In order to understand the context of this song’s lyrics, we need to remind ourselves it’s 1997 pop punk is at the peak of its all-time popularity. The Offspring have broken through to the mainstream. Green Day have broken through, and a bunch of bands on Bad Religion’s Epitaph Records label like NOFX and Rancid and Pennywise were all selling millions of albums at this point. So punk rock more than any time in history, included in the late 70s when the genre was invented, was more popular than ever. And so NOFX puts out this song called “The Desperation’s Gone” and here’s the lyrics to that song:

Turn, tune the knob K-go

Some alterna radio

Strategic marketing hype, media, stereotype

Has our music been castrated? Yes

To you it may sound good

To me it sounds so wrong

The notes and chords sound similar

The same forbidden beat, but

The desperation’s gone (the song’s the same)

But the desperation’s gone

Okay, so we’ve got Fat Mike, the lyricist here, talking about turning on K-rock radio. That’s the big LA rock radio station that often breaks new music, and also uses media hype and stereotype, perhaps, to sell punk rock to the masses. And what Fat Mike is saying is here is that he’s turning on this pop radio and he’s hearing punk rock, but it sounds castrated to him. It doesn’t sound real. It may sound good to people who don’t know punk, but it sounds wrong to him. The notes and the chords are the same. They’re doing some three-chord punk. That same “forbidden beat.” That forbidden beat is punk rock bass-snare-bass-snare-bass-snare super-fast; that’s the punk beat. And so the song is the same. The chords are the same. The notes are the same. The beats are the same, but the desperation is gone.

Part of the core power of punk rock is desperation, passion, emotion, and hunger. And when we do something like watch the Foo Fighters performing “Holiday in Cambodia,” the Foo Fighters haven’t been hungry for anything years. They can’t be hungry for success. They’ve been successful for decades. They can’t be hungry for money. They have more money than they could ever have. They can’t be hungry for food. They’ve gotten more food than they can ever want. The Foo Fighters live a comfortable life.

Whereas when Dead Kennedys were performing “Holiday in Cambodia” in 1980, they were a hungry bunch of kids. They were hungry for a lot of things: hungry for change, hungry to express themselves, hungry for success, and probably hungry to get food on their table. Punk Rock kids in the early 80s didn’t always have a bunch of food being handed to them the way the Foo Fighters do. And all of this bleeds into the music and into the performance. The desperation, the roughness of it is what makes it so powerful. And when you get a bunch of millionaires, these legendary and successful musicians, together covering the same song, it’s not the same because the desperation is gone.

And so if you are one of those writers out there describing yourself as a perfectionist, I wish that you would put a little more energy into being hungry, as opposed to being perfect. Get a bit more desperation on the page.

I think so many writers, especially new writers, spend way too much time trying to get things perfect when, instead, what you should be doing is getting your emotion on the page.

What are you hungry for? What do you want to make the reader feel? How do you want to change the world with your storytelling?

Steven Pressfield once wrote, “Write your first draft like the devil is behind you.” And I think what he’s talking about there is writing with desperation not with perfection in mind.

All right, that was me kind of riffing on some of the ideas I touch base on in my book, Smash Fear and Write Like a Pro. It’s a tiny little thing. You can read it in one sitting, and it’s really going to help you push through some of these fears that so many writers face, including fear of releasing work that isn’t perfect in your mind.

Thank you so much for tuning in. Hit that subscribe button and I will see you on the next episode The Writing Coach.